Lately, I’ve been sinking into the song “Skrting on the Surface” by the Smile. I listen to it a few times a day. It feels ineffable and ephemeral and wise, a wispy ode to skating on the thin ice of life before we slip under the surface. Perhaps my gloss makes the song sound gloomy, but I hear a soft sense of wonder. Yes, we’re skirting on the surface, but that means we’re still amazingly alive.

I think you can glimpse flashes of that wonder by watching footage of the Smile performing on NPR’s Tiny Desk. At the start of “Skrting on the Surface,” I love how Thom Yorke lets the music move through him. He opens himself to Jonny Greenwood’s sly arpeggios and Tom Skinner’s subtle snare and cymbals. At first, he sings without words, just sounds. His falsetto wavers, and his hand waves in time to the music.

One way to hear the opening lines of “Skrting on the Surface” is “When we realize, we have only to dive, / then we're out of here.” This feels like an acknowledgment of everything glimmering below the surface, the mystery and beauty beyond what we can see. We live most of our lives on the surface, but we might see flashes of the expansiveness beyond the surface.

I’ve been a “good enough” Zen Buddhist for about twenty-five years. (Here, I’m riffing on D. W. Winnicott’s concept of the “good enough parent.” I meditate daily, know a handful of Buddhists, and dip into teachings and talks when I feel pulled to do so.) During meditation, I often have a sense of the flimsiness of the surface, its impermanence but also how it connects to everything else. I find something beautiful in that flimsiness, impermanence, and interconnectedness. It reminds me of a haiku by Issa that I read in my early twenties:

This world of dew

is only a world of dew

and yet

(Translation by Sam Hamill.)

When another Buddhist asked me what type of Buddhist I was, I quoted this haiku and said it encapsulated my sense of Buddhism. And, honestly, this sparse poem has informed my worldview since I read it in the late 1990s. I want to live in the “and yet.” (If you’ve read my novel Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian), you might recall that I included a poem that hinges on the phrase ‘and yet,’ which is an homage to this haiku.) I think “Skrting on the Surface” also gestures towards Issa’s “and yet.”

Indeed, scientists have discovered that less than 5% of everything in the universe is observable matter; the remaining 95% are composed of dark energy (~68%) and dark matter (~27%). Clearly, we are ontologically and objectively skirting on the surface.

Last year, I released a song called “Ontology Blues” that also points to the “and yet”-ness in Issa’s short, incandescent poem:

What is this?

What even is this?

The mystery, the trembling, and the beauty

At the time, I was often meditating on the koan-like question, “What is this?” This universe is so weird. What the actual fuck is it? When I’d go for a walk in the morning along the seawall, I’d look out at the water, the mountains, the sky, the clouds, the distant skyline of my city, the people ambling around me, the trees, the water birds, the harbour seals that sometimes surfaced and gazed at me with their dark, round eyes. “Hey, friend,” I’d say softly as we exchanged glances. Like, what the heck is this goddamn fucking place where we’re living? When “Ontology Blues” tumbled out of me, I think it conveyed some of my sense of wonder at finding myself alive, a vulnerable, wide-eyed creature with consciousness, in this unfathomable universe.

In Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals, Alexis Pauline Gumbs writes about the harbour seal, which can slow her heartbeat from 120 bpm to three or four bpm when she dives under the water’s surface. Gumbs adds:

When she is underwater, the oxygen she needs is the oxygen she has. Her blood breathes for her through her muscles as she descends as deep as 1,500 feet. Deep enough for what she needs to do. She slows her heart and listens, reaches, knows.

What if you could hear the world between your heartbeats? Slow down enough to deepen into trust. How can I learn the skill to tell my heart slow down? The pressure is coming. Slow down and we will have the air we need. Slow down and trust the ocean underneath you.

Another way to hear the opening lines of “Skrting on the Surface” is “When we realize, we have only to die, / then we're out of here.”

More than one person I cared about died unexpectedly in 2022. We never know how long people in our lives will be here, just as we don’t know how long we’ll live. I sometimes meditate on my own death. I know I’m going to die, but I don’t know when. What should I do? (To be clear: I want to live as long as possible. That said, I’m not afraid of dying.)

I love Scout Nesbitt’s song “Your Beat Kicks Back Like Death,” which I hear as a meditation, an incantation, a warning, and a celebration:

We're all gonna die

We're all gonna die

We don't know when

We don't know how

We're all gonna die

We're all gonna die

I was talking to another queer writer recently, and we both admitted to weeping constantly throughout 2022. I experienced deep loss, but also found myself so grateful for having known and been changed by people who passed.

Fifty years ago, Yoko Ono wrote the following in a New York Times article called "Feeling the Space":

The odds of not meeting in this life are so great that every meeting is like a miracle. It’s a wonder that we don’t make love to every single person we meet in our life. We take meetings like riding a cab. You know that you would probably never meet the driver again. Yet if the car crashed, that driver is the person you are going to die with. In fact, your life is in the driver’s hands while you’re in the car. But when you get to the destination, you give a bit of metal and slam the door behind you.

I’m reminded of acoustic biologist Katy Payne’s description (on the On Being podcast) of the absolute delight elephants sometimes take in seeing one another, even if they’ve only been separated briefly:

“When a group of elephants that has been separated even for a few hours comes together, we would see members of the group on different sides of the clearing, and we would say, ‘Oh, they’re soon going to meet,’ so we would focus our cameras and our attention on one of them. When they met, it was the most marvellous show of total New Year’s Eve, family-reunion excitement, as if they’d been apart for years. But actually, it was only since ten o’clock in the morning. They rush together, twirl their trunks together, roar, urinate, defecate, flap their ears, and the whole thing says that each individual is overcome with excitement.”

When I mentioned this description recently to a friend I hadn’t seen in person in a couple of months, she said that she’d felt some of that elephant-like, trunk-twirling joy when she came down to meet me in the lobby to go for lunch. “I get to spend time with Hazel!” It’s so sweet to be able to tell people that we adore them and appreciate them. Since the pandemic hit, I’ve been telling people in my life much more openly that I love them.

At the end of 2019, I decided to try writing a memoir. It was going to be kaleidoscopic and would take the form of a triptych, touching on three aspects of my life. I soon realized that it hurt too much to write about my life, especially from the ages of six to twenty-six. For that entire span, I was so angry, anxious, and afraid. It felt like I’d been born without skin. Everything felt like too much. I hid inside myself, like a hermit crab. While trying to write, I remembered Harry Crews talking about writing his memoir A Childhood: The Biography of a Place: “I thought if I could relive it and set it all down in detailed, specific language, I would be purged of it.” But the writing process proved harmful rather than helpful. “It almost killed me, but it purged nothing,” he wrote. “Those years are still as red and raw and alive in my memory as they ever were. So much for good ideas.”

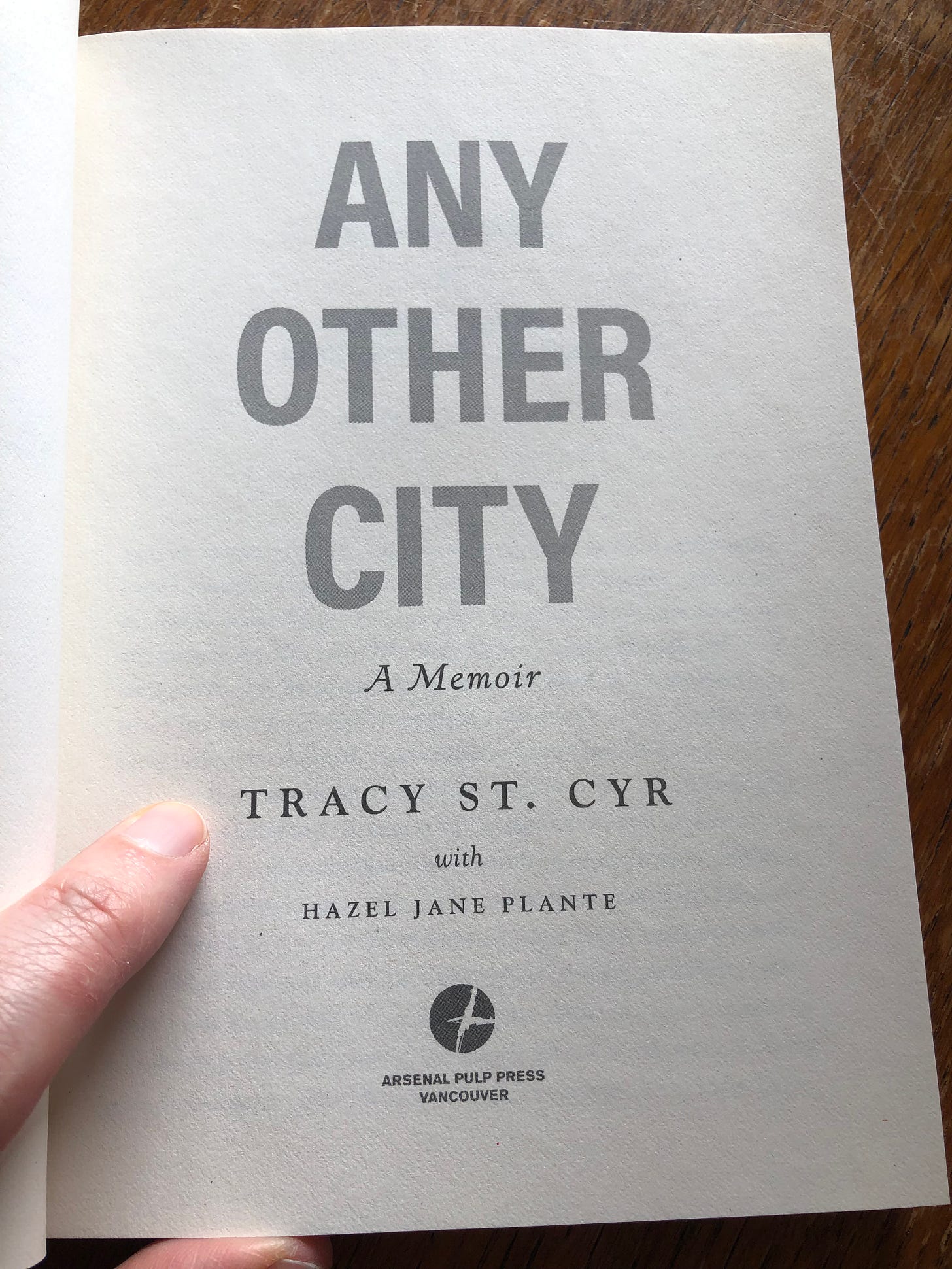

After a month or so, I abandoned my memoir and wrote Any Other City, the fictional memoir of a trans femme musician, a book that allowed me to transmute some of my own recent and distant trauma through the cushion of fiction.

Tracy St. Cyr, the narrator of Any Other City, writes a song called “Broken Open,” which is about the space that sometimes appears after you experience something devastating. Eventually, new things start to emerge after an interval of anguish and blankness, just as small green stems grow from a nurse log after a forest fire.

In “Skrting on the Surface,” Thom Yorke sings “When we realize that we are broke and nothing mends / We can drop under the surface.” I keep thinking he’s reminding himself of the energy thrumming below the surface, the way everything is interconnected below this fractured facade. But it’s also true that some things break and can’t be mended. Last year, I lost my centre of gravity and found myself unexpectedly unmoored. It felt like the sutures on a deep wound, one that had never truly healed, had unravelled overnight. I became a gunmetal grey cloud formation bucketing rain. I became a tippy row boat on choppy waters. I wept constantly. I felt alone and adrift. Lines from two songs swam through my mind for several months:

From Scrawl’s “Story Musgrave (At the Piano)”: “Disintegrate and move on.”

From Neil Young’s “For the Turnstiles”: “Though your confidence may be shattered / It doesn't matter.”

These looped lines proved to be good company. Day after day, I disintegrated and moved on. Month after month, I kept disintegrating and moving on. I let myself feel shattered and saw that it truly didn’t matter. As Pema Chödrön writes in When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult Times, “To live is to be willing to die over and over again. From the awakened point of view, that’s life.” I was definitely awake.

And perhaps there’s something beautiful in that, like the final stanza of Jane Hirshfield’s "For What Binds Us":

And when two people have loved each other

see how it is like a

scar between their bodies,

stronger, darker, and proud;

how the black cord makes of them a single fabric

that nothing can tear or mend.

I find that last line so barbed and so beautiful.

And, as Alexis Pauline Gumbs reminds us in Undrowned, our scars are merely scratches on the surface:

And your scars are not all I know about you. And my scars are not all I want you to know. And your name is made where life makes itself in me. And your name is medicine over my skin. And our kinship is the kind of salve that heals whole oceans. And love is where I know and do not know you. And love is where we began and where we begin.

One of my favourite people in the world died last year. She was the first person who came to mind whenever I did loving-kindness meditation. She was a lovely, loving presence in my life for over twenty years, even after I transitioned, even when I inadvertently broke the heart of someone she loved, even when her memory started to fade. She always surprised me by telling me how pretty I was, even with my shaved head and my lack of makeup. I loved her so much, and I’m profoundly grateful that our lives overlapped for so many years.

I think about those people who come into our orbits and change our lives. These catalysts are often people we’re close to, but sometimes brief encounters can shift our trajectories. Another person who died last year, someone I only knew briefly, changed me. We went on four socially-distanced dates in August 2020, when the pandemic felt particularly intense. (For context, this was a few weeks after the B.C. Centre for Disease Control recommended lovers “Use barriers, like walls (e.g., glory holes), that allow for sexual contact but prevent close face-to-face contact.”)

We were both wary of getting involved, but we were queer women who enjoyed spending time together. I was thrilled when she invited me to her apartment for cocktails; the windows would be open, the fan would be going, and we’d keep our distance. I even agreed to go on a beach date, and I’m not a beach person. I remember how hard it was to tell if we had chemistry. I’d never dated when it felt risky to sit side-by-side, let alone when kissing felt riskier than oral sex. In the end, we didn’t wind up dating. Everything felt too fraught, and we drifted back to our usual lives, agreeing to be friends. We texted occasionally, mostly about books.

But she changed my life in a few small ways. She was one of those rare people with a clear, calm sense of self and no fear of missing out. I only know a few people who I consider wise, but she seemed wise. I’m hesitant to say much about her because she was a private person, intentionally avoiding all social media platforms. (When I searched her name online, only a handful of work-related things came up.) I keep writing sentences about how she affected me, but I keep deleting them. Perhaps meaningful changes are tricky to track. It’s easier to describe the visible surface than the invisible undertow.

In “Skrting on the Surface,” Thom Yorke sings, “We have only to click our fingers, and we’ll disappear.” For me, those lines are tinged with sadness and magic. Yes, we can disappear in an instant. We can vanish from the thin surface of this life into thin air. Like watching a magician turn a donut into a smoke ring. For me the magic is that we get to live at all. At one point, the narrator in my novel Any Other City thinks to herself, “There are countless ways to coexist on this pale blue dot, and yet humans are choosing to create this cockeyed world. How strange. How disheartening.” We tumble into this unfathomable universe in these glorious bodies, and we keep choosing the most myopic and shitty options available. What the actual fuck?!

I wonder if an underlying problem is thinking of ourselves as separate. We see our thin film of skin as delineating the tiny cosmos that we live in, forgetting we’re connected to everything else.

Indeed, the two songs that spun in my head for months on end — Scrawl’s “Story Musgrave (At the Piano)" and Neil Young’s “For the Turnstiles” — kept reminding me that it was my puny ego that was disintegrating, that was shattered. Over time, I found a new centre of gravity. It was somehow heavier and airier, located lower and less tethered to my ego. Maybe the thin surface we’re skirting on is ego, which keeps us separate, obscuring the interconnectedness of everything.

Before being released by the Smile, this song had been played in different versions over the years. At an Atoms for Peace show in 2009, Thom Yorke played a lovely solo piano version of “Skirting On The Surface”, which has an airy, unfussy feel. (Right before playing the song, he chided someone in the crowd, “Hey, loudmouth: shut the fuck up, alright,” which is an inauspicious segue into the song. But he soon finds his footing at the piano. As Nigel Tufnel says in Spinal Tap after being besieged by disappointing snacks before a gig, “I’ll rise above it. I’m a professional.”)

When Radiohead played it live for the first time in 2012, Thom Yorke said, “This song is called ‘Skirting’ or ‘Skating on the Surface’; I’m not sure.” The Radiohead version has a surprisingly clunky arrangement. It’s like a plane that never takes off. It taxis on the runway for five meandering minutes. I’m puzzled by how every aspect of the song seems to be so wrong. Somehow none of it works: the bass line, the backing vocals, the tambourine, the guitar parts, the lumbering tempo. Towards the end, Thom Yorke starts dancing, and even his dancing feels fucked up. I’m not sure what to call this dance. The Funky Puppeteer? The Tipsy T-Rex? I think he was just embracing the energy of fucked-up-ed-ness that overtook his song. I imagine him thinking, “Why not dance like a goofball while my band flounders around inside this song?”

From my late teens to my early twenties, I released several lo-fi albums under the name sparse. I wrote and recorded hundreds of songs. It was how I kept myself afloat. Often the writing process happened during the recording process. I’d find a few chords and a few words and hit ‘Record’ and just fumble through the song, letting words come out of my mouth before I could consider them. Some of the songs were good. Some of them were not so good. But they helped me keep my head above water.

At the start of 2023, I found myself rereading Jimmy McDonough’s biography of Neil Young, Shakey. While discussing the recording of Tonight’s the Night, Neil Young says to McDonough, “I don’t worry about the permanence of the record. That’s what’s good about it. You make it, you got it, that one’s too late to change, you do another.” That’s so perfect. Treat songs like snapshots. Elsewhere, he talks about adapting the idea of cinema vérité to the recording studio: “The original thought was audio vérité. Why not make records like that? Capture the moment.”

At times, Neil Young seems intent on capturing the mercurial moment of when the band discovers the song. You don’t really know how to play piano? Perfect, you’re on piano for this song! And there is so much magic on Tonight’s the Night. (I’m not sure I’ve ever admitted this before, but “Albuquerque” is a song that I listened to endlessly in my early twenties. I felt it in my body. Ben Keith’s steel pedal playing is dolorous and delicious. The lyrics are so spare and evocative. And I adored the drawn-out way Neil Young sings “Albuquerque,” turning it into a hilarious and glorious ten-syllable-long melody. I was so angry at having been born and desperately wanted to disappear or escape or transmigrate, and this song soothed me. For four minutes, the clouds cleared and everything felt spacious. For the last few years, I’ve often turned to Alice Coltrane’s “Om Shanti” when I need a sonic balm.)

One of my favourite moments in Shakey is when Denny Purcell describes Neil Young playing back different takes to Nicolette Larson, who sang harmony on a song: “Neil’s got three faders of her. And he said, ‘Now, Nicolette, this is the best vocal you did’ – pushes up the fader – ‘and now here’s the next best one’ – pushes that fader up – ‘but here’s the one we’re gonna use, ‘cause we like the feel.’” I hope Nicolette Larson was okay with the take they released, but I agree that music is really about capturing the feel of the moving moment.

During the pandemic, I noticed that I missed releasing music. In mid-2019, I’d started playing music on and off with a couple of friends, but I sensed we wouldn’t be releasing anything for a while. In September 2020, I found myself making songs how I used to in my twenties, writing and recording them the same day with one or two takes. Any flaws became part of the song. My first album, which I released when I was 18 or 19 years old, was called Flawed Beauty. (Fun fact: It was 90 minutes long! I wrote most of the dozens of songs on it while taking classes at Camosun College or during my long bus commute.)

At the time I recorded this batch of new songs, I was enamoured with “Too Small to Fail” by Forgetters, which includes the line “I’m a lioness when it comes to you.” I called the project lo-fi lioness. So far, I’ve released twenty lo-fi lioness songs.

My band, Certain Women, has also started releasing music. The first song we released is a recording of the first time we played the song “All the Pretty Ghosts.” I think it was one of those rare moments of capturing the song while we were inside it.

Earlier this month, we released a four-song EP called Useful and Beautiful. The title track is one of my favourites, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the third track, “Hold Me Like I’m Not on Fire.” Its title comes from an illustration by my talented writer/artist pal John Elizabeth Stintzi. It’s a song that I didn’t fully understand when I wrote it. That’s often my experience with art: it’s wiser than the person who made it. In retrospect, I can see how much this song had to teach me about hurting and healing. I don’t always love my voice, but I like how vulnerable I let myself be when I sang the repeated line “Hold me.” And I like the feel during the lines “Can you feel it? / There’s a power,” how I stop strumming my guitar and Jay’s bass throbs below the surface.

My songs often orient me. At the end of 2022, I found myself writing a song called “The Opening,” which felt auspicious. As with many songs, it started in one place and kept meandering, blooming into something wilder than I’d anticipated. I often think about the National song “Pink Rabbits,” which is a nearly perfect song, aside from its “lightning” / “frightening” couplet. When I write a song lately, I’ll sit with each line and each word. ”Is this a lightning / frightening couplet? What word doesn’t work?”

Like many of my songs, I think it’s about love, death, and pleasure. As “The Opening” started tilting towards death at the end, I was a bit surprised. At some point, I felt the line “cradle my skull in your hands” emerge, which paired nicely with the earlier phrase “lay your head in my lap.” Ending “The Opening” with death suddenly felt inevitable because it begins with conception and birth (“We all begin with an opening”). The final lines of the song quote D. T. Suzuki’s final words on his deathbed: “Don’t worry. Thank you, thank you.”

I think my favourite moment in the song starts by evoking Rainer Maria Rilke and Fred Moten and ends by exalting sexual pleasure. (Rilke: “Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror. Just keep going. No feeling is final.” Fred Moten: "Anybody who thinks that they can understand how terrible the terror has been, without understanding how beautiful the beauty has been against the grain of that terror, is wrong.")

I’ve known beauty, and I’ve known terror

I’ve felt empty, and I’ve felt pleasure

So praise your hearts and praise your lungs

Praise your fingers and praise your tongues

I hear myself sing these lines, and I want to laugh. But, you know what, I have known beauty and terror, emptiness and pleasure; I’ve lived several lives, and I maybe it’s okay for me to be wise and whimsical — and wanton.

In the early days of the pandemic, I listened endlessly to “New Town” by Life Without Buildings. I find that song so soothing, elliptical and beautiful. I’d often listen to Sue Tompkins when I needed a burst of energy. (In particular, I think there’s something so mesmerizing and sexy when she sings again and again and again about looking in your eyes. She’s repeating; she’s insisting; she’s here, facing you, looking in your eyes. You’re staring at each other. This is happening. I also need to mention that I recently discovered there is live footage of Life Without Buildings, and it is amazing.) When I started writing a novel, I gave it a placeholder title that I’d cribbed from Life Without Buildings’ only album: Any Other City.

Dear friends, I have held Any Other City. She is gorgeous. Now is what I’m considering “the pregnant pause,” that span of time between knowing she exists and when other people get to meet her. That will happen in April. Yay! (By the way, if you want to review my novel, email marketing@arsenalpulp.com to get a print or a digital copy.)

I’m so excited and delighted to be bringing Any Other City into the world in the near future. Maybe when we see each other, we can roar and twirl our trunks (in our N95s, ofc). I fucking love you. <3

Upcoming events

January 25, 7pm (Pacific): Queers in Winter with Oliver Baez Bendorf, Michael V. Smith and Hazel Jane Plante. UBC School of Creative Writing event. Hosted by Sarah Leavitt. Mode: Online via Zoom.

February 26, 4pm (Pacific): I’ll be reading with five other writers. I’ll post details on the events page of my website when I know them. Mode: Online.

April 15, 8pm (Pacific): Music, Words, and Buster Keaton at the Shadbolt Studio Theatre, Burnaby, BC. Featuring two Buster Keaton films (The Balloonatic and Sherlock Jr.), a live musical score by Róisìn Adams, and a talk by Onjana Yawnghwe and Hazel Jane Plante. Mode: In person.